For more than two millennia, the city of Toledo has sat on the top of a granite hill surrounded like a horseshoe by the River Tagus, just 40 miles from Madrid. The present day Alcazar (castle) stands where there was a Roman fortress. Jews were a part of Toledo’s history since the last years of the Roman occupation in 192 BCE.

For more than two millennia, the city of Toledo has sat on the top of a granite hill surrounded like a horseshoe by the River Tagus, just 40 miles from Madrid. The present day Alcazar (castle) stands where there was a Roman fortress. Jews were a part of Toledo’s history since the last years of the Roman occupation in 192 BCE.

The Jews existed peacefully with the Romans and were always an important part of the city. They became known as money-lenders, merchants of fine cloths and precious metals and intellectuals, and were generally well-respected by the other peoples of Toledo. For centuries, scientists, philosophers, poets and artists of widely differing backgrounds met in Toledo to exchange ideas.

In 507 CE the Visigoths made Toledo their capital, adopting Catholicism in 589 after the Third Council of Toledo. From then on a series of anti-Jewish laws were enacted until the Muslims conquered the Visigoths in 711. Christians, Jews and Muslims, three ethnically distinct communities, then lived together in the city until the conquest of Cordoba in 1085 by Alfonso VI, a Christian ruler. For economic reasons, as well as for their knowledge of Arabic language and customs, Alfonso needed the Jews, who remained in Toledo under the protection of the monarchs.

By the Middle Ages the city had been conquered by the Moors, and was a stronghold during the emirate of Cordoba and an imperial city in the times of Carlos V, a melting pot of Christian, Jewish and Moslem cultures. Listed on the World Heritage List in 1986, Toledo was officially granted Heritage of Mankind status by UNESCO in 1987.

Many of us know Toledo as a center of Jewish Spain in the 12th, 13th and 14th centuries. Toledo was the capital of Cordoba and a united Spain before the capital was moved to Madrid in 1561. A trip to Spain is like walking in the footsteps of our favorite Sephardi heroes, Moses ibn Ezra, Samuel Nagrella, Jacob ben Aser, Halevi and Maimonides.

In Toledo we find street names such as Calle Juderia and Calle Samuel Ha-Levi among the small narrow streets of the medieval area. Synagogues were built with no special architectural features on the exterior. Under Moorish rule, the Jews adopted the Mudejar style of mosques. Under Christian rule, the synagogues could not exceed a certain height. There are three remaining synagogues in Spain, two of them in Toledo and one in Cordoba. All sit on a city square.

During the 12th and 13th centuries, Jews and Christians of Toledo were free and equal in the eyes of the courts and they had the benefit of royal favor. The members of the Jewish community formed the “aljama” headed by a rabbi named by the king. The rabbi was the spiritual leader of the community and was in charge of maintaining order and the supervision of judicial affairs according to the Talmud and the Torah. Judges, a chief of police and a bailiff were elected yearly.

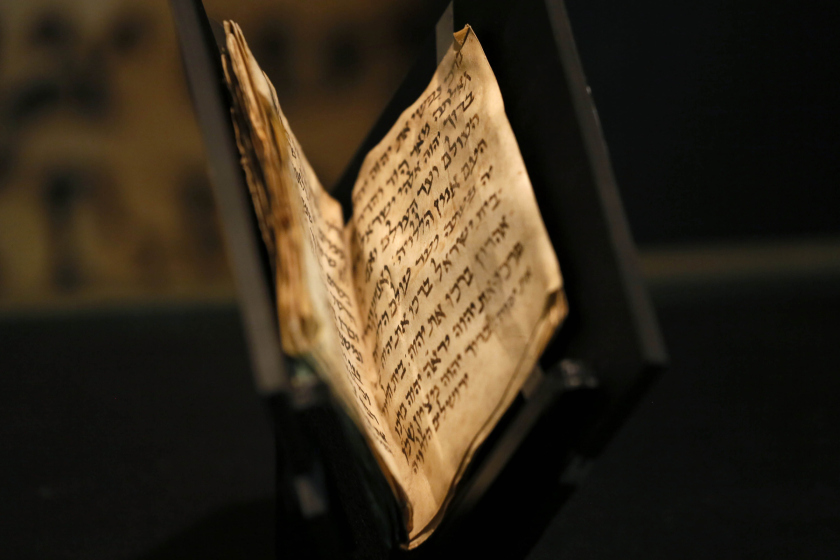

In 1391, there were five Talmudic schools and 10 synagogues in Toledo. As Spain works toward reviving its Jewish past, many visitors flock to Toledo to see the two remaining synagogues, the El Transito Synagogue and La Sinagoga de Santa Maria La Blanca, along with the Sephardic Museum. Both synagogues were built in the Mudejar style, heavily influenced by Arabic aesthetics, and were converted into churches after the expulsion of the Jews in 1492 by Ferdinand and Isabella.

The Juderia, or old Jewish Quarter of Toledo, was the center of rabbinic teachings. Jewish scientists and doctors thrived in the 14th century as Jews were treated well by the Christian monarchs of the time. But there were persecutions over time, especially at the hands of common Christians who persisted in telling tales in which Jews were the villains.

The Jewish Quarter also housed the famous Escuela de Traductores de Toledo (School of Translators), whereby Jews used their knowledge of Arabic and Hebrew to translate philosophical and scientific works into Latin and Spanish.

Still standing and a popular tourist attraction, La Sinagoga de Santa Maria La Blanca was completed in 1203 by Yosef ibn Sosan under the reign of King Alfonso VIII. Yosef was the king’s principal tax collector and prince of the Jews in Castile. The synagogue is a small plain rectangular building measuring 72 x 55 feet. There are 32 columns inside that support the arches along five parallel aisles. There are no Hebrew inscriptions on the walls, as this custom did not begin until more than a century after the Sinagoga was built.

During the reign of King Alfonso VIII the Jews enjoyed the favor of the king, who was in love with a Hebrew woman. The synagogue was the center of Jewish life in Toledo until 1405, when there was a riot against the Jews and it was converted into a church named Santa Maria La Blanca.

El Transito Synagogue was built in 1366 by Samuel Ha-Levi, who was financial advisor to King Pedro I of Castile, better known as Peter the Cruel. Ha-Levi built the synagogue at his own expense in an attempt to build a house for the G-d of Israel comparable to the destroyed Second Temple in Jerusalem. Years after the synagogue was built, Ha-Levi fell out of favor with King Pedro, who had him beheaded in Seville.

A walk through Toledo will generally end at the Cambron Gate, formerly known as the “Gate of the Jews” due to its proximity to the Jewish Quarter.

Other important Jews of Toledo during this period were Abraham ben Alfakhar, a doctor and poet who carried out diplomatic missions for Alfonso, and Salomin ibn Zadok, who was charged by Ferdinand III to collect taxes for the king of Granada.