Jews first appeared in Morocco more than two millennia ago. The first substantial Jewish settlements developed after the destruction of the First Temple in Jerusalem. The Jews lived in relative tranquility, allowed to maintain their status as a distinct nation until Constantine made Christianity the law of the land in the 4th century. The Jews were held in contempt until the Muslims conquered the land in the 7th century.

Jews first appeared in Morocco more than two millennia ago. The first substantial Jewish settlements developed after the destruction of the First Temple in Jerusalem. The Jews lived in relative tranquility, allowed to maintain their status as a distinct nation until Constantine made Christianity the law of the land in the 4th century. The Jews were held in contempt until the Muslims conquered the land in the 7th century.

As early as Roman times, Moroccan Jews had begun to travel inland to trade with groups of Berbers. Jews lived side by side with Berbers, forging both economic and cultural ties. When the Muslims swept across the North of Africa, Jews and Berbers defied them together. Across the Atlas Mountains, legendary Queen Kahina led a tribe of 7th century Jewish-Berbers in battle against encroaching Islamic warriors. Though the Muslims defeated Kahina and converted her ancestors to Islam, many Berber communities remained.

As they did elsewhere, Muslims in Morocco made a clear distinction between “believers” and “infidels.” Jews in Islamic societies became dhimmis, second-class citizens, who were allowed to practice their religion but did not have equal rights. The Muslims forced the Jews to wear a yellow sash, prohibited them from building synagogues taller than a mosque and owning horses and did not allow them to drink wine in public or perform religious rituals in public. They also had to play a head tax (djezya) and a property tax (kharaj).

As they did elsewhere, Muslims in Morocco made a clear distinction between “believers” and “infidels.” Jews in Islamic societies became dhimmis, second-class citizens, who were allowed to practice their religion but did not have equal rights. The Muslims forced the Jews to wear a yellow sash, prohibited them from building synagogues taller than a mosque and owning horses and did not allow them to drink wine in public or perform religious rituals in public. They also had to play a head tax (djezya) and a property tax (kharaj).

Muslims forced urban Jews to live in ghettos called mellahs. As a result of this segregation the Jews educated their own, leading to a high literacy rate, much higher than that of the Muslim community. Some Jews excelled in business, further separating themselves from the rest of Muslim society.

The Moroccan Jewish community experienced a population explosion in the 15th and 16th centuries as Inquisition exiles fled from Spain and Portugal. The Spanish Jews were very different from the North African Jews, but they tolerated each other, sharing both customs and meager resources. Ottoman Turks tolerated the Jews. When most Moroccan Jews welcomed the French declaration of the Moroccan Protectorate 1912, which made them Moroccan citizens, frustrated Muslims reacted by massacring Jews in the mellah. A fierce independence rebellion broke out in 1947 on the heels of subsequent Vichy French and Allied occupations of North Africa. The independence movement succeeded in 1955. As Morocco’s new Muslim government became more friendly with the Arab League, the Jewish position grew more uncertain; Jews tried to escape from Morocco but government troops captured and jailed them. In 1961 King Hassan II gave the Jews the right to emigrate, and a substantial percentage did.

Today there are several thousand Jews in Morocco, most of whom live in Casablanca. There are pockets of Jews in cities like Fez, Rabat and Marrakesh, and a continued Berber-Jewish remnants in small villages like Inezgane. Contemporary Moroccan Judaism is a blend of Oriental, Berber, Arab, Spanish customs, resulting in a variety of practices that combine Rabbinical teachings with a devotion to spiritualism unfamiliar to most Western Jews.

Today there are several thousand Jews in Morocco, most of whom live in Casablanca. There are pockets of Jews in cities like Fez, Rabat and Marrakesh, and a continued Berber-Jewish remnants in small villages like Inezgane. Contemporary Moroccan Judaism is a blend of Oriental, Berber, Arab, Spanish customs, resulting in a variety of practices that combine Rabbinical teachings with a devotion to spiritualism unfamiliar to most Western Jews.

The Talmud began to influence Moroccan Judaism even as Jewish scholars were writing it in the 2nd to the 5th centuries. Talmudic scholars like Rabbi Akiva traveled extensively in North Africa, spreading Jewish scholarship to all parts of Morocco; even in distant villages in the Atlas Mountains there were rabbis discussing the Talmud. Moroccan Judaism developed along Talmudic lines and therefore resembles Western Judaism more than that of the pre-Talmudic Ethiopian Jews.

The synagogue was the center of activity in the Moroccan Jewish community. Each community had a chief rabbi who preached, taught Judaism and gave advice; the cantor would lead the congregation in prayer. Each Jewish community had its own rabbinical court which had some autonomy over Jewish law and was sometimes able to negotiate with authorities to soften anti-Semitic proclamations. The Museum of Moroccan Judaism, one of the only institutions of its kind in the Arab world, was reopened in Casablanca recently after months of renovations.

The re-opening ceremony was attended by Moroccan government officials, the museum’s president Jaques Toledano and Samuel Kaplan, the US Ambassador to Morocco and a past president of the Minneapolis Jewish Federation.

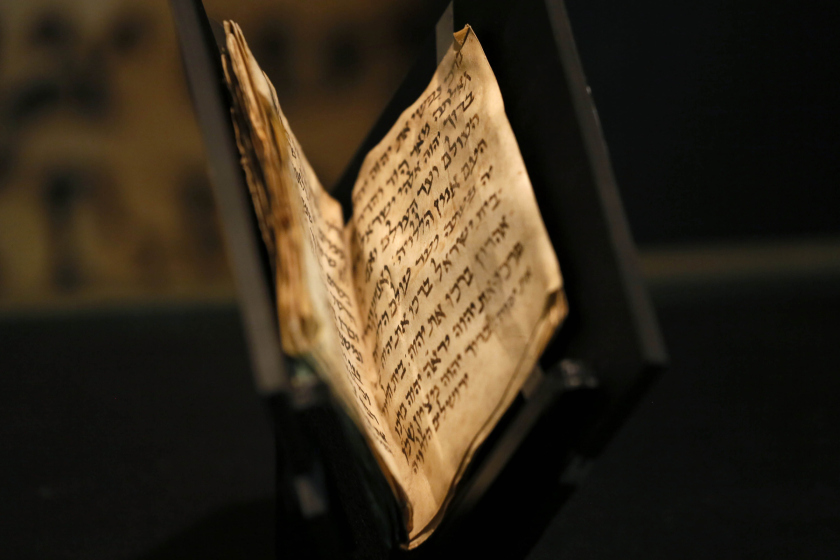

The halls of the museum were filled with the sound of violins and the scent of incense and orange blossom. The museum features photos of synagogues from across the kingdom, Torah scrolls and Hanukah lamps, Moroccan caftans embroidered with gold; jewels ancient rugs and various objects of Jewish-Moroccan cultural heritage.

The halls of the museum were filled with the sound of violins and the scent of incense and orange blossom. The museum features photos of synagogues from across the kingdom, Torah scrolls and Hanukah lamps, Moroccan caftans embroidered with gold; jewels ancient rugs and various objects of Jewish-Moroccan cultural heritage.

“It’s not a fancy museum, but it contains some real treasures,” said Joel Rubinfeld, co-chair of the European Jewish Parliament.

The museum was created by the Jewish Community of Casablanca in 1997 with the support of the Foundation of Jewish-Moroccan Cultural Heritage. It uses world-class standards of conservation for its national and international collections and presents religious, ethnographic and artistic objects that demonstrate the history, religion, traditions and daily life of Jews in the context of Moroccan civilization.

There is a large multipurpose room, used for exhibitions of painting, photography and sculpture and three other rooms, with windows containing exhibits on religious and family life (oil lamps, Torahs, Hanukah lamps, clothing, marriage contracts (ketubot) Torah covers) and exhibits on work life. In addition, there are two rooms displaying complete Moroccan synagogues, a document library, a video library and a photo library.

The Museum offers guided visits, sponsors seminars and conferences on Jewish-Moroccan history and culture, and organizes video and slide presentations.