The Jews of Italy have a history that spans 2,000 years. Many groups of Jews, driven out of their native countries, Spain (1492), Portugal (1498) and Germany (1530) were welcomed there and created a strong and well-organized community, which became one of the most flourishing and important in Italy.

The Jews of Italy have a history that spans 2,000 years. Many groups of Jews, driven out of their native countries, Spain (1492), Portugal (1498) and Germany (1530) were welcomed there and created a strong and well-organized community, which became one of the most flourishing and important in Italy.

The Dukes of Este, in the 15th century, wanted to strengthen the economic condition of their country. The growing need for credit facilitated the settlement of Jews, who were originally money-lenders, but later became retailers, manufacturers, and tradesmen.

The Jews were given autonomy and although they were permitted to dwell anywhere in the city, most of them lived in the same area.

Soon Ferrara attracted more Jews, including many Maranos from Portugal, who could openly practice Judaism. The Christian population gladly received the newcomers, since they were wealthy and intelligent and they helped develop the commerce of the city, by bringing Spanish wools, silks, and pearls from India. They stimulated the export trade and the population of Ferrara grew rapidly.

After 1492, houses of prayer for Sephardic services were built, and the German Jews opened a synagogue in one of the existing houses of prayer. Each congregation had its own rabbi.

In the early 1500s, Pope Paul IV took away many of their rights, but in 1534 all of their privileges were returned. Maranos were granted permission to practice their religion and the expelled Jews of Naples and Bologna found refuge there, as did the Maranos from Ancona.

In 1570, the community had 10 houses of prayer. That year there was a terrible earthquake; churches and monasteries tumbled down, but in none of the 10 houses of prayer and small sanctuaries, was divine service interrupted. The Jews regarded this as a sign of divine protection. Those who owned houses, courts, or enclosed gardens, opened them and cared for those affected by the earthquake, clothed and fed them.

A rabbinical society was organized in 1573, for the education of rabbis and teachers. The prosperous condition of the Jews came to an end when, in 1597, when the pope became ruler of Ferrara. About one half of the Jewish population moved to Modena, Venice, and Mantua.

Permission to engage in trade was renewed in 1598; but the Jews were not allowed to keep animals or own real estate. All property had to be sold within five yearsa provision which was carried out in 1602. The number of synagogues was limited to one for each rite; and for the permission to sustain them, the Jews had to pay a tax. They were allowed to have only one cemetery.

Other enactments, with the sole purpose of mortifying the Jews and lowering them in the eyes of the populace, were issued. The severest measure which the papacy ever adopted against them was the establishment of a ghetto. From 1626 to 1627, the Via Sabbioni, Via Gattamarcia, and Via Vignatagliata, where the greater part of the Jews had lived for many years, were enclosed by five gates erected at their expense. All Jews had to live there.

In 1797, at the instance of French General Latner, the gates of the ghetto were torn down. Unfortunately, two years later, Austrian troops entered the city and all the old laws were enforced. The French returned to restore liberty in 1802. Full freedom was given for religious worship.

During the 1700s and 1800s many Jewish organizations were formed. Each had a specific purpose. One provided for the daily minyan and study; another made sure the poor were cared for, another supplied candles in cases of death; and still another was established to give lectures on Shabbat.

After several years of freedom, the ghetto gates were once again restored and closed on January 13, 1826 by Leo XII. Many of the old enactments were enforced and numerous Jews moved to Tuscany. The following year, the Jews were prohibited from leaving the city without permission and from owning real estate. Finally, in 1831, the gates of the ghetto were torn down, and the Jews received the same rights as other citizens.

With the election of Pope Pius IX, the Jews asked to be granted emancipation. In 1849 they were given full citizenship. Some Jews were at once elected to the Consiglio Comunale (City Council).

On May 12, 1863, 31 delegates met in Ferrara to protest against the frequent forcible baptism of Jewish children. They further proposed to make religious instruction obligatory, in order to promote a sense of religious duty; to disseminate good books on Jews and Judaism; and to found an Italian rabbinical seminary. Their resolutions remained without effect, however, and the congress which met at Florence in 1867, at which Ferrara was again represented, was equally unsuccessful.

In 1943, after the northern part of Italy was occupied by German soldiers, most of Ferraras small Jewish community was sent to the death camps. Out of 183 deportees, only one returned to the city. The names of those lost are on two epigraphs which are set on the side of the door to The Museo Ebraico di Ferrara (The Jewish Museum of Ferrara) reminding visitors of the victims of the Holocaust.

The Jewish Museum of Ferrara is located at number 95 on Via Mazzini, in the building where the citys original synagogues still stand. The building dates back to 1485 when it was built on a field donated to the community by Samuel Melli. The three synagogues inside the building still hold events, which makes them the oldest synagogues in Italy still working in the places of their origin.

The house, before the Second World War, was indistinguishable from the others, except for its bigger size. In the entrance-hall a small staircase leads to the Fanese School, a small synagogue of the 19th century still in use, where there are precious pieces of furniture dating back to the 18th century.

From the courtyard, where there are pillars used for the celebration of Sukkot, the main staircase begins. Upstairs there is the German School, still in use, that in the past was the Ashkenazi Synagogue. Inside there is a 17th century altar decorated with a floral motif and stucco decorations on the walls dating back to the 19th century. Above the entrance a grating protects the Womens Gallery, which is no longer in use. Another flight of stairs leads to the halls where the Rabbinical Court and the great hall of the Italian School once were. All the rooms have memorial tablets and some of the furniture is original; other pieces come from places of worship which dont exist any longer.

Visitors to the Museum can go into the three synagogues. On the upper floors of the building, four rooms have been created. In the first room there are objects on display from different ages, which are ordered according to the various celebrations in Jewish religious life.

On the right hand side a small synagogue with antique furniture has been reconstructed. Among the pieces is a 15th century bench and a multi-colored carved Arn from the community in Cento.

In the second room there are objects on show in eight display-cases, representing the celebration of eight feasts. On the sides of the room there are mainly silver objects on display.

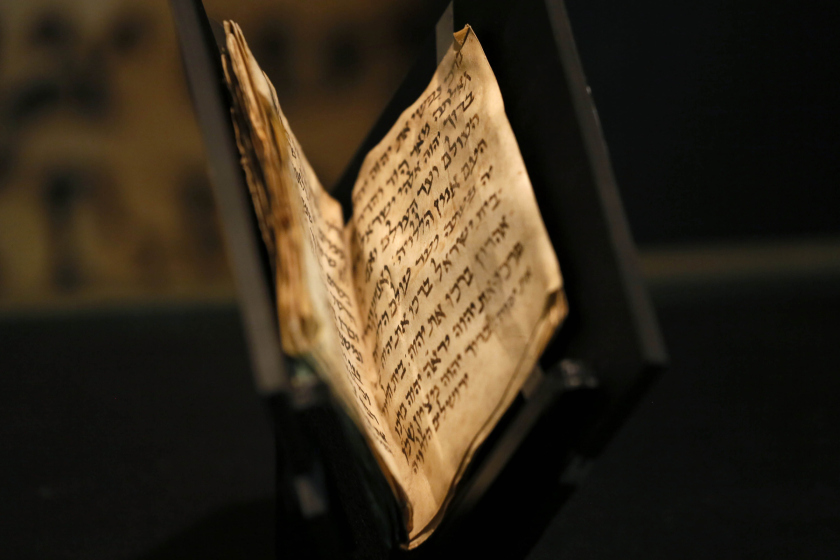

The third and fourth rooms display objects and documents which illustrate, and give specific evidence of, the Ferrara Jews from the distant past to the present day and emphasize the significant links with Italian and European history. There youll find original 18th century editions of the work of the Ferrara Talmudist Isacco Lampronti and two books published by Abraham Usque, one of the major Jewish printers in Renaissance Ferrara. Of particular interest are the keys which were used to close the doors of the Jewish ghetto.

Throughout the years, thousands of Jews called the ghetto their home. When walking through the Jewish Quarter and the museum, you can almost feel them with you. The next time youre in Italy, spend a day strolling through Jewish history.