A Lost Community Walks Through Its History

In February 2025, a remarkable event unfolded in Damascus: members of Syria’s Jewish diaspora returned to their ancestral homeland after decades in exile. Led by Rabbi Yosef Hamra and his son Henry, this delegation sought to reconnect with their roots and assess the state of Jewish heritage sites in the Syrian capital.

The Jewish presence in Syria dates back over 2,500 years, beginning with the Assyrian exile in 722 BCE, when Jews from the Kingdom of Israel were deported to various parts of the Assyrian Empire, including Syria. Another significant wave of Jewish settlement followed the Babylonian exile in 586 BCE, when Nebuchadnezzar II destroyed the First Temple, leading many Jews to settle in cities such as Damascus and Aleppo. By the Hellenistic and Roman periods, Syria had thriving Jewish communities, as noted by the historian Josephus, who described large Jewish populations in Damascus, Antioch, and other cities. In 1170, the Jewish traveler and scholar Benjamin of Tudela visited Damascus and recorded the presence of 10,000 Jews, highlighting their organized community and economic influence. The 1492 Spanish Expulsion brought Sephardic Jews to Syria, particularly Aleppo and Damascus, further enriching Jewish life and establishing these cities as key centers of Jewish scholarship and trade in the Middle East.

For the Hamra family, returning to Damascus was deeply personal. Rabbi Yosef Hamra dedicated over 40 years of his life to serving the Jewish community of Damascus in multiple roles—as a rabbi, hazan, mohel, shochet, sofer, schoolteacher, and principal—until the day they left Syria. Even after leaving, he has continued to serve the community to this day. In 1992, after years of restrictive policies under President Hafez al-Assad, the Chief Rabbi of the Syrian Community, Rabbi Abraham Hamra A”H, met with Assad and secured permission for the Jewish community to leave the country without restrictions. This marked the beginning of a mass exodus of Syrian Jews, reducing the once-thriving community in Damascus to fewer than ten individuals. The fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in December 2024 created a rare window of opportunity, prompting the Hamras to return and reconnect with their roots.

Stepping onto Syrian soil after so many years was both emotional and bittersweet for the delegation. They walked through the familiar yet changed streets of the Old City, greeted by the sights and sounds of a Damascus that had endured years of conflict. Though much had transformed, remnants of Jewish history still stood—some preserved, others in ruins. The Jobar Synagogue, once a central place of worship and a symbol of Jewish presence in Syria, had been reduced to rubble, a casualty of war. The Al-Faranj Synagogue, though still standing, bore the scars of neglect. Even more heartbreaking was the state of the Jewish cemetery, which had been overtaken by garbage and debris, with crumbling tombstones and displaced grave markers scattered among the rubble. The sacred resting place of generations had become an unkempt wasteland, its sanctity eroded by years of disregard. The delegation also learned that decades earlier, a highway had been built through the cemetery, relocating graves and damaging many tombstones. For the visitors, seeing such desecration was a painful reminder of how history can be forgotten when there are no caretakers left to protect it.

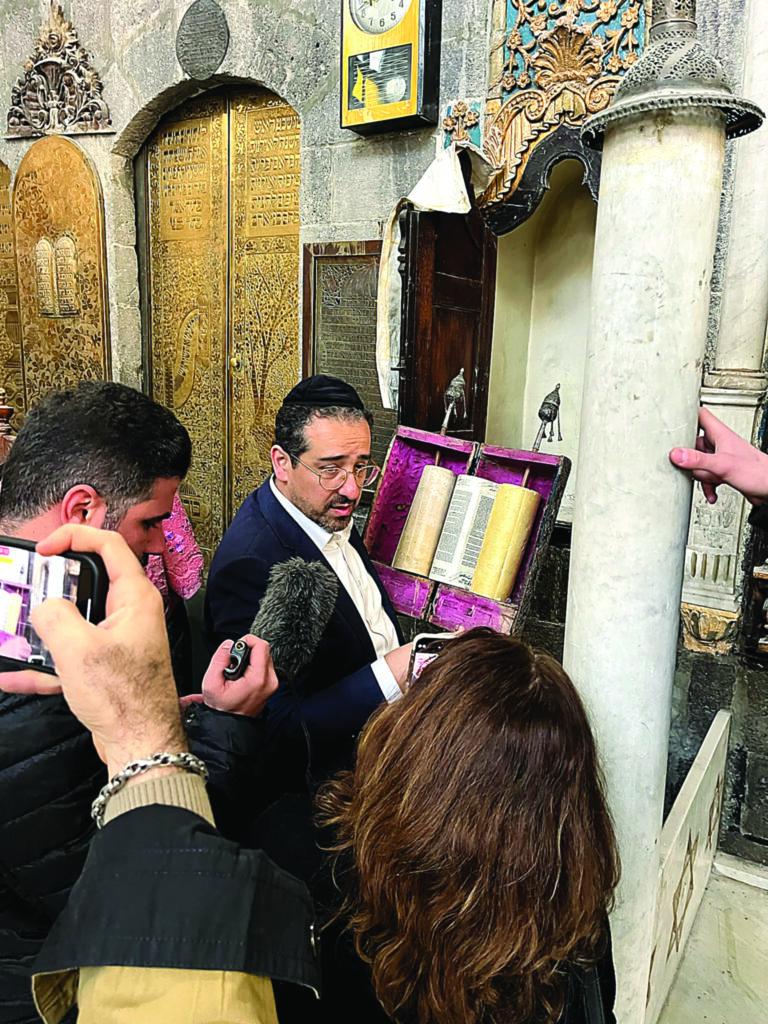

As they arrived at the Al-Faranj Synagogue, stepping through its doors for the first time in over 30 years—where Rabbi Yosef Hamra and his late brother, Rabbi Abraham Hamra A”H, had once served as hazanim—he simply whispered, ‘Wow, wow, wow.’ The moment was overwhelming. Dust-covered pews lined the walls beneath peeling paint. Ancient prayer books, hundreds of years old, lay untouched under a discarded prayer shawl. Henry Hamra, now a cantor, stood in the same space where his father had once led prayers. His voice trembled as he recalled, “I remember my father, the last day that we—before we left here, he was praying, crying when he was praying the last prayer over here.”

The delegation had hoped to hold a formal Jewish prayer service at the synagogue—the first in decades. But Jewish law requires ten adult Jewish males for a minyan, and even with some of the few remaining Syrian Jews, there were not enough. Instead, Rabbi Yosef and his son stood together and recited personal prayers, filling the silent sanctuary with the echoes of their voices, just as they had decades before.

Despite the destruction and loss, the returning Jews were met with warmth. Many locals, both Muslim and Christian, remembered their Jewish neighbors and shared stories of coexistence. Walking through the Jewish quarter, they ran into former neighbors from 30 years ago who greeted them with open arms. The Syrian government also signaled its willingness to welcome back members of the Jewish diaspora, with one official telling the delegation, “This is their home, and the government will help restore property and citizenship.”

During their visit, the delegation met with Syrian officials to discuss the preservation of Jewish heritage. With the country in the early stages of rebuilding, the fate of religious and cultural sites remained uncertain. The government expressed its commitment to protecting these landmarks, but the challenges were immense. Years of war had not only destroyed buildings but had also displaced entire communities, making large-scale restoration difficult. Some of the visiting Jews expressed interest in supporting these efforts, believing that even if the Jewish community in Syria would not return in significant numbers, its 2,500-year-old legacy must be preserved.

For Rabbi Yosef and Henry, this visit was about more than history—it was about the future. Would there ever be a Jewish revival in Syria? Could young Jews, raised in countries like the U.S. and Israel, find a way to stay connected to their Syrian roots? These were difficult questions with no immediate answers. As Henry reflected on their visit, he remarked, “This city is still part of who we are, no matter where we live. We may not return permanently, but we can never forget where we came from.”

Upon returning to New York, Henry was frequently asked what he hoped to achieve from the trip. His response was clear: “My goal is to preserve history. I want Jews from around the world to come visit these holy places. I want people to be able to visit the family plots of their parents, grandparents, and past generations. Just as people visit the graves of great rabbis in Israel, Uman, and Morocco, so too should they visit the ancient synagogues and the holy graves of revered Syrian rabbis. Most notably, the great Kabbalist Rabbi Chaim Vital is buried here.”

The next trip to Damascus is already being planned for the end of April 2025. Rabbi Chaim Vital’s yahrzeit falls on the 30th of Nisan, which this year corresponds to April 28, 2025, and there are plans to visit his grave on that day. If you are interested in joining this trip or getting involved in the restoration and preservation of Jewish sites in Damascus, please email Henry Hamra at HenryHamra@gmail.com.

revealing Torah scrolls that were left behind when the Jewish community fled Syria in the 1990s, as the government forbade them from taking them