Being raised in Aleppo in the latter days of World War II and during the creation of the State of Israel was not easy. Syria is a Muslim country, partly Christian, and the idea of a Jewish state in its midst was horrific to the Muslim governments of the Middle East.

Being raised in Aleppo in the latter days of World War II and during the creation of the State of Israel was not easy. Syria is a Muslim country, partly Christian, and the idea of a Jewish state in its midst was horrific to the Muslim governments of the Middle East.

Aleppo is in the northern part of the country. The land was flat and dry. The weather was mild, although colder in the winter as Aleppo is far from the Mediterranean Sea. Jews had lived in the region for over 3,000 years, long before the Jews of Spain arrived.

Aleppo’s Jews lived in a variety of housing. Landowners lived well, but most families were poor. They lived in large Spanish-style homes, which were divided. Each family had a few rooms and bathrooms were shared with another family.

What had once been a prosperous area for Jews, who could trade their goods along the caravan route to the East; Aleppo became depressed when the Suez canal opened in 1869.

By the 1890’s, this area, which housed tens of thousands of Sephardic Jews for three millennium, became an unbearable place to live. The Ottoman Empire, which controlled the region for centuries and left the Jews to govern themselves, had weakened considerably.

By the 1890’s, this area, which housed tens of thousands of Sephardic Jews for three millennium, became an unbearable place to live. The Ottoman Empire, which controlled the region for centuries and left the Jews to govern themselves, had weakened considerably.

There were few opportunities left for the Jews. Many of them left to go to the World’s Fair in France. With this taste of the rest of the world in their mouths and hearts, many left for America or London and its streets paved with golden opportunity.

They ranged from upper class bankers, farmers, landowners and merchants to grocers, peddlers, craftsmen and stall keepers. Slowly, these Arabic-speaking Sephardic Jews began heading west, taking ships from France to America, stopping in the cold inhospitable halls of Ellis Island, before arriving on American soil.

The arrival in America and initial adjustment period for Aleppo’s Jews was not easy. Ashkenazic Jews made fun of these Jews who spoke no Yiddish and pronounced Hebrew in such an uncivilized way. Food was a problem as they were housed with Ashkenazic Jews who ate heavy foods like stuffed cabbage, and Middle eastern food was initially not available.

As more and more Aleppoan and Damascene Jews arrived in America, things became easier. This group eventually acculturated to American ways and became established into the community we have today.

Most Jews had left Syria by the 1930s. Syria had approximately 15,000 Jews within its borders by the end of World War II. Most of the Jewish population had fled to America, Palestine, South America and other places during the first quarter of the 20th century. The class system practiced by Syria’s Jews disappeared over time as fewer and fewer Jews remained in Aleppo and the community became smaller.

The few thousand that remained lived from hand to mouth. The community owned much land and someone had to stay behind to care for it. Others were too poor to save for a ticket. Times were rough. In 1947, the Syrian government condoned a pogrom against the Jews by Arabs and Christians. During the pogrom, the two Talmud Torahs and the synagogue were burned. Luckily, no lives were lost.

In the 50s, conditions for the Jews got even worse. The government placed travel restrictions upon them. They weren’t allowed to attend universities or institutions of higher learning, and could not hold government jobs nor obtain driver’s licenses. Their limited education forced most men into retail sales and trades. They opened small stores and sold textiles and other items. Here again the government placed a severe restriction on the Jews—no imports of merchandise.

By the 60s the travel restrictions became tighter. Jews could not travel more than three miles from their homes without permission. And the Syrian government initiated a curfew against the Jews. They had to be in by 9:00 pm and could not leave their homes again until 5:00 am the next morning.

The Chief Rabbi and his committee depended on the money sent from Near East Jewish Affairs to take care of the poor, the sick, hospitals, doctors and pharmaceutical needs. The organization was called Tzedakah Um Marpe.

Among others, Chief Rabbi Yomtov Yedid had a heavy hand in controlling the religious direction and leadership of the entire Jewish community. Times were difficult economically. People were very poor and the ability to earn a living was limited due to the political conditions. Contributions from the community, even from the well-to-do, to support the Talmud Torah and other community needs were limited.

Rabbi Yedid was faced with many obstacles and challenges each day. He was the driving force that kept the community together. Keeping the faith, keeping the Sabbath, and strict observance of Kashrut were essential despite the economic and political conditions.

There were three Jewish quarters where Jews lived in Aleppo: Djamalie, Beth Nassy and Bahsita. Bahsita is where the Great Synagogue of Aleppo still stands. It is believed to have been constructed by King David’s general, Joab ben Seruya, in 950 BCE, after his conquest of the city. The shul houses the tomb of three Tzedakim, which remains intact today.

There were two Talmud Torahs in Aleppo. Only boys attended until the late 1950’s when girls began attending school. The children attended school in small classes of 20. Education was of a very high standard and children were expected to meet those standards.

Four rabbis were the most recent principals of the Talmud Torah and guided the quality of education. They were Rabbi Izhak Shehebar, formerly Chief Rabbi of Argentina, Rabbi Yosef Shasho, who now lives in Panama, the late Rabbi Faraj Sasson who recently passed away in Brazil, and Rabbi Tzedakah Harari now Chief Rabbi of Mexico.

Children attended school seven days a week. From Sunday through Friday they went from 8:30 am to 6 pm with a one hour break from 1 pm to 2 pm and a shorter day on Friday to prepare for the Sabbath. On Saturday, children went to shul and then to school, where they studied Torah until 1:00 pm. Discipline and respect were taught at an early age. During July and August, children attended school from 8:30 am. until 1:30 pm.

Here again the government took control. Muslim principals were assigned to the Talmud Torahs to watch the management and education in the schools, a practice that continued until the schools were closed.

By the mid-60s, there were less than 5,000 Jews left in Syria, most of them in Aleppo. President Hafez Assad came to power and slightly eased the restrictions on Jews, allowing them to attend universities and obtain drivers licenses. But Jews attempting to leave the country were jailed, outraging the Jewish communities of the world.

In the early 70s the American press reported the conditions of Jews: CBS aired a story on 60 Minutes by Mike Wallace, telling of the restrictions placed on the Jews. He spoke of the two jailed men and the fact that President Assad would not allow Jews to leave the country, largely due to the belief that they would go to Israel and join the army to fight against Syria.

The government was good to the citizens, including the Jews, in many ways. Food was subsidized, attendance at the universities was free of charge and most did not pay taxes. For much of the 70s, the Syrian government received bad publicity for not allowing its Jews to leave the country.

By the early 1990s President Assad became convinced that the Jews should be allowed to leave on the condition they go to America and not Israel. They began leaving by the hundreds filling up airplanes as fast as they could get out and arriving at New York airports into the hands of Brooklyn’s Syrian community.

Today’s Syrian immigrants have established themselves in Brooklyn’s Syrian Sephardic community, many of them professionals, all religious—bringing with them the Syrian dialect of Arabic, lost to the younger generations, and the ways of the old country, reminding us of the traditions practiced by our grandparents.

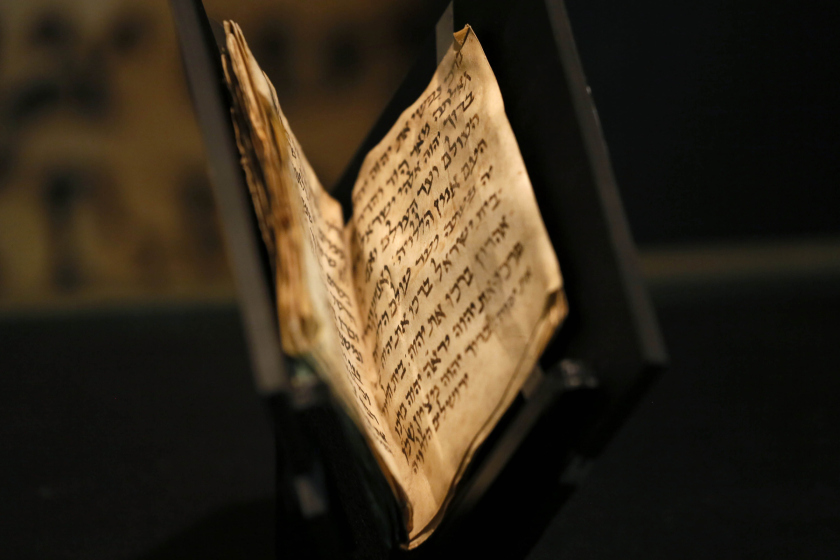

Brooklyn’s Syrian American community uses the books written by Rabbi Jacob Kassin. The prayer books are written according to Aram Soba, the traditions of the Jews of Aleppo. Many of the traditions practiced today in the community are 2,000 years old.

The Syrian government declared all synagogues historic monuments—they cannot be torn down. As time wore on the Old Synagogue in Aleppo went to ruins. In 1979, several community members who remained, began to renovate the old synagogue, completing only a portion.

Today, Syria is not a place that is safe for Jews to visit. Future attempts at peace in the Middle East may alleviate this restriction, allowing Sephardic Jews from the region to return and research their roots.