CLEMENT SOFFER

THIS IS THE THIRD INSTALLMENT OF MY FAMILY’S EXODUS FROM EGYPT, CLEMENT SOFFER’S LIFE STORY. THE FIRST ARTICLE BEGAN WITH CLEM, A TEENAGE BOY, HAPPY, LIVING IN EGYPT WITH LOTS OF FRIENDS. IT ENDED WITH BOMBS FALLING AND CLEM ARRIVING HOME TO FIND OUT HIS FAMILY WAS SAFE. LAST MONTH, WE READ THAT 60,000 JEWS WANTED TO LEAVE EGYPT. THIS MONTH YOU’LL LEARN HOW CLEM HELPED MANY FAMILIES FLEE AND WAS ALMOST HUNG FOR IT.

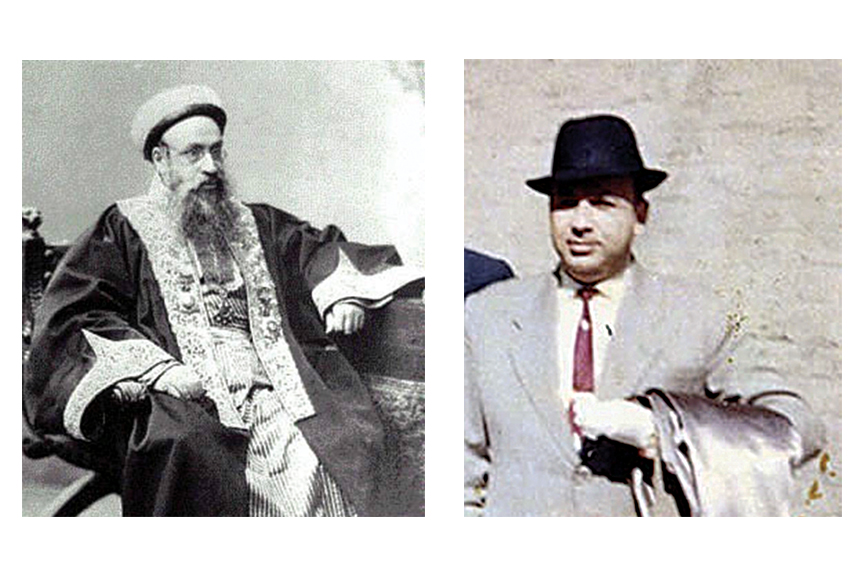

The Rabbinate was run by the Chief Rabbi of Egypt, Rabbi Haim Nahum Effendi. When he became blind, Rabbi Abraham Choueka, a highly educated rabbi from the Sorbonne, became his substitute when it came to all official matters. It fell on his shoulders to help the Jewish community leave Egypt and to protect and safeguard the poorer members of the Jewish community who did not have the means to escape. I knew Rabbi Choueka, as he had been my Hebrew school teacher.

At the time, all the Jews wanted to leave Egypt and although Rabbi Choueka had a few helpers, his office, which was in the Rabbinate, was very poorly staffed. They were not able to handle the thousands of requests for certificates. Each certificate needed extensive research.

Rabbi Choueka asked my father for my help (I was 15 at the time). He told him I would need to search the archives of the Rabbinate and fill out the required forms, then bring them to him for his signature. Once that was done, the members of our community would be able to take these forms to the Mogamaa, the governmental building, in order to get exit visas to leave the country.

I accepted, and so I would spend each day searching the archives then bringing them to Rabbi Choueka. Several other young men were doing the same task.

I did this research job from the middle of November in 1956 until the end of December, when one day the Rabbi called us into his office. He explained that the poorer Jews in the Jewish ghettos (about 5,000) could not afford to leave and were being tortured, raped and killed. He asked us to volunteer to ask the Jews who lived in the European quarters of Cairo, where Jews were relatively safe, to allow a family from the ghetto to stay with them.

So, I went from being a researcher to making phone calls to wealthy Jews. I explained that they would be saving the lives of the poor people and explained that they would return to their own homes as soon as the country stopped persecuting them. The community responded well, taking the poorer Jews in. Unfortunately, this did not last long. Shortly thereafter the Rabbinate started receiving complaints from the homeowners that they were having too many conflicts with the people they had taken in and demanded that they be returned to their ghettos, or at least get them out of their homes.

Returning them to the ghettos meant their probable demise at the hands of their neighbors. But, in order for them to leave the country, they would need proper transit papers and visas from the country where they would go, plus travel expenses which they did not have. In order to obtain these documents, each person needed to provide to the government accurate records certifying their birth, marriage, or the death of family members who were their caretakers. In addition, they needed to show proof of legal residence in Egypt, and paperwork explaining an acceptable reason for leaving Egypt. Egypt would not approve their papers until they had a visa from an accepting country.

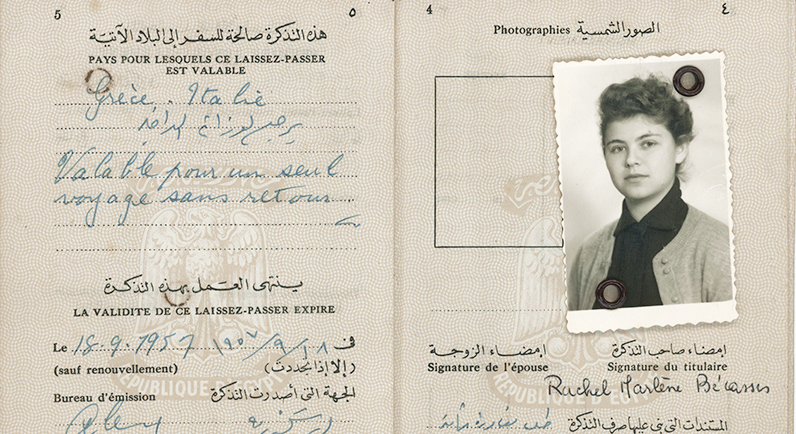

Thus, I had to submit documentation to convince immigration officials in another country that the persons were in imminent danger, and that they had a valid need to immigrate according to the requirements of the accepting country. Once the visa was obtained, it had to be shown to the Egyptian officials with the paperwork describing the reason they were leaving before their travel would be approved. The paperwork had to list a person’s name and contact information from the accepting country who could be contacted by Egyptian authorities to verify they would not be returned to Egypt. This was important because once a person was approved to leave, their passport would be destroyed, and they would no longer be allowed back. Egypt did not want to deal with any returnees if things fell through. So the authorities scrutinized all documentation carefully, not out of concern for the people, but because they did not want any problems to be “taken upstairs,” a situation that could get the agent fired or worse.

My job was to take on the full responsibility for these families, to prepare them with all documentation for exiting Egypt as soon as possible. (Of course, there were other volunteers doing this as well.) At a meeting with Rabbi Choueka, we were told to visit embassies in Cairo, and explain that there were 5,000 Jews living in ghettos who were in great danger. We were advised to remind embassy staff of the Holocaust, the slaughter of the Jews by Hitler and his cohorts. I had to negotiate with the staff for visas for different families, once visas were issued, I was to help them process their exits.

Once all the proper documentation was completed, reviewed, and checked for accuracy, I would take them to the Mogamaa Exit Department Ministry building and present them to an officer in charge of reviewing and approving all the documents. Some of the Jews were illiterate and signed the forms with a big X. I, or another volunteer, would We always accompany these families to the Mogamaa to them fill in government applications, to serve as witness, and to make sure the families were being approved to exit the country. I was there for so many families that I lost count. I was driven by the desire to help other Jewish human beings.

Whenever an Egyptian officer would give us a hard time before issuing an exit visa, we were told to explain that these where extremely poor people who would be a great burden on Egypt in terms of financial support, hospitalization, education, clothing, and a long list of other needs. Of course, Egypt had never provided such support to anyone of the Jewish faith, but it was a convincing scenario. We said if the wealthy Jews left Egypt they wouldn’t support the poor Jews any longer so the government would have to. Many people were issued visas.

Sometimes an officer would give me a hard time arguing with my explanations. Then I would have to offer a bribe, sometimes as much as 5 to 10 pounds to receive a visa. It was always amazing to me how quickly a few pounds would convince an agent to overlook their staunch objections with the paperwork. It was my first lesson in how money greases the gears on which the world turns.

My responsibility to the families didn’t end until they were in taxis on their way to Alexandria, where they would board ships to their new country. Once one family was on their way, I was reassigned to another family.

Several months passed with this continuous exit of Jews from the ghettos, while more well-to-do Jews were being evicted from their homes, and their businesses sequestrated. It was a chaotic time, Jewish families were being broken apart, separated by travel, and run out of the country in fear of being arrested. If there was no reason to arrest them, they’d be accused of spying for Israel. This kept the Egyptians calm and preoccupied. They thought the Jews were the cause of the unrest in the country, while the reality was the officers all the way to the president were robbing the country of its resources, finances, businesses and creating shortages of food due to their lack of knowledge and inefficiency to replace the Jewish and foreign businessman.

One day, after 3,000 Jews had exited Egypt, the Rabbinate received a visit from the Neyabah or government security police. They met with Rabbi Choueka, informing him that sending those 3,000 Jews out of the country was against the best interest of Egypt and he must cease and desist. He added that all volunteers must stop helping the poor Jews depart or face arrest for being traitors. The Rabbi worried about the additional 2,000 Jews that were still in the ghetto and would be left to fend for themselves. He told us not to worry about the Egyptian government, so we went back to helping out at the Rabbinate to research the archives and issue certificates.

Two weeks after that visit, the Rabbi called us into his office again and asked for volunteers to continue this life saving work, but under different circumstances. He informed us that he had contacted the Swiss Red Cross and we would be working out of their office as volunteers for human rights causes. Once there, we would be under their shield and protection as humanitarian workers. He informed us that we should cut all relations with the Rabbinate and we would be issued identification papers as Red Cross volunteers. There, we could continue trying to get the remaining 2,000 Jews out of the ghettos.

The Rabbi thought that Egypt would not dare challenge the Swiss Red Cross, but he left the choice to us. One volunteer dropped out, but the rest of us stayed. Our mornings started at the Red Cross office in Cairo. We continued to do our work but whenever we went into the Mogamaa with another family ready to depart, the investigation was much more serious, our bribes were refused by the officers, but they had no choice but to let the families leave.

This continued until we almost had everyone out of Egypt. There were just 25 families left. Many years later I learned that those 25 Jewish families made it out of Egypt, thanks to the help of Swiss Red Cross employees.

What happened the day it stopped? I was followed into the metro on the way home and was arrested and accused of being a spy for Israel. They claimed that because I had Egyptian nationality, and I was responsible to the Egyptian government, I was acting against the interests of Egypt, despite my explanation that I was a Red Cross employee and a human rights activist.

The interrogation was a horror, too painful to describe. I was at the whim of young officers trying to make a name for themselves. If they found a spy, a promotion was guaranteed and I would be hanging in a public square and my entire family would disappear. They told me that if I signed a document that they put before me, I could go home to my parents. I refused to sign it for fear that my family would be arrested, or worse, and that I would hang in the public square. I spent eight hellish hours being tortured and beaten, but I refused to sign.

At the 8th hour a Red Cross representative arrived with an officer from the Interior Ministry and ordered my release, since my arrest was causing an international calamity.

I was relieved that the beatings had stopped. Instead of being hung, I was given a travel pass which the police stamped: “Dangerous for the public security,” and I was sent to Greece. I had five dollars in my pocket and no skills — my future looked bleak.