BERTHA SABBAGH

IT WAS IN 1975. I WAS 4 OR 5 YEARS OLD WHEN MY FATHER MADE THE IMPULSIVE DECISION TO GET US OUT OF BEIRUT. HE SAID THE GUNFIRE WAS GETTING TOO CLOSE TO HOME AND THE WAR WAS TOO BIG TO IGNORE. MY MOM, MY BROTHER, SISTER AND I, DID WHAT HE SAID, WE ALWAYS DID WHAT HE SAID.

He packed us up in the car and drove us upstate to Bhamdoon. My sister remembers him stopping the car as we left home, walking right up to the soldiers, face-to-face and literally asking them to hold fire so he could get his family through. They did, and we did. Many people know how the story ends. That night a bomb fell on our house, destroying everything in it.

That was the first time that my father saved my life. We stayed in Bhamdoon for weeks, maybe months, I have no idea. During that time, the cast that I had on my arm from a playground accident weeks before, needed to be removed. My dad took a saw, and sawed it off. No doctor, no X-ray, no consultation; just his confidence to do it, and my wholehearted trust in him. He did it. Then, we played a game. He stacked coins on my elbow and asked me to try to catch them with my hand. Primitive physical therapy I assume, but to me it was a game. He’d stack coins and I would try with futility to catch them. We both laughed. My arm healed just fine.

It is literally the only memory I have of ever playing a game with my father. It’s the only memory I have of laughing with him. At that time and ever since, he was always in survival mode. Surviving the war, the challenges to build his life over again, and the obstacles of life as a refugee. His survivor instincts were always on high alert. It was how he was able to save us so many times since, including the time he convinced someone at the airport to make us a passport, on the spot, so we could board a plane to Egypt—just hours before the airport shut down in 1976.

When we finally got to America and for years and years after, my father had no time for love or fun. The game of physical therapy he played to heal my broken arm was a distant memory. He was obsessed with securing our future. The fear of losing everything again consumed him. He didn’t understand work–life balance, and made providing for us his priority—above everything else—sometimes to a fault, to his detriment and to ours. I remember when he started buying merchandise from China for his wholesale business. He did everything the hard way in an effort to save every penny. For example, he sold plastic headbands and calculated that it was cheaper to ship them to America if he bought them flat without packaging. For years, this was a weekly activity—he would boil a pot of water on the stove, and then one by one he would dip the flat plastic headbands into water to make them malleable and then shape them into headbands. The four of us waited in an assembly line. One would pack the headband into a clear poly bag, two would attach the header card with staples and the last would pack it into cartons by the dozen. I could not have been more than 10 years old. Until today, I don’t know if I am really proud to tell that story or really ashamed of it, but it was the reality of my childhood.

Ironically, his obsession with making money was never about buying fancy things. He lived a modest life and had zero interest in expensive cars or fancy homes. He never bought or wanted gifts and never indulged in anything. He was a deep rooted bargain hunter. His drive wasn’t about money ever. It was a vow to secure us financially. This was the fear that motivated him.

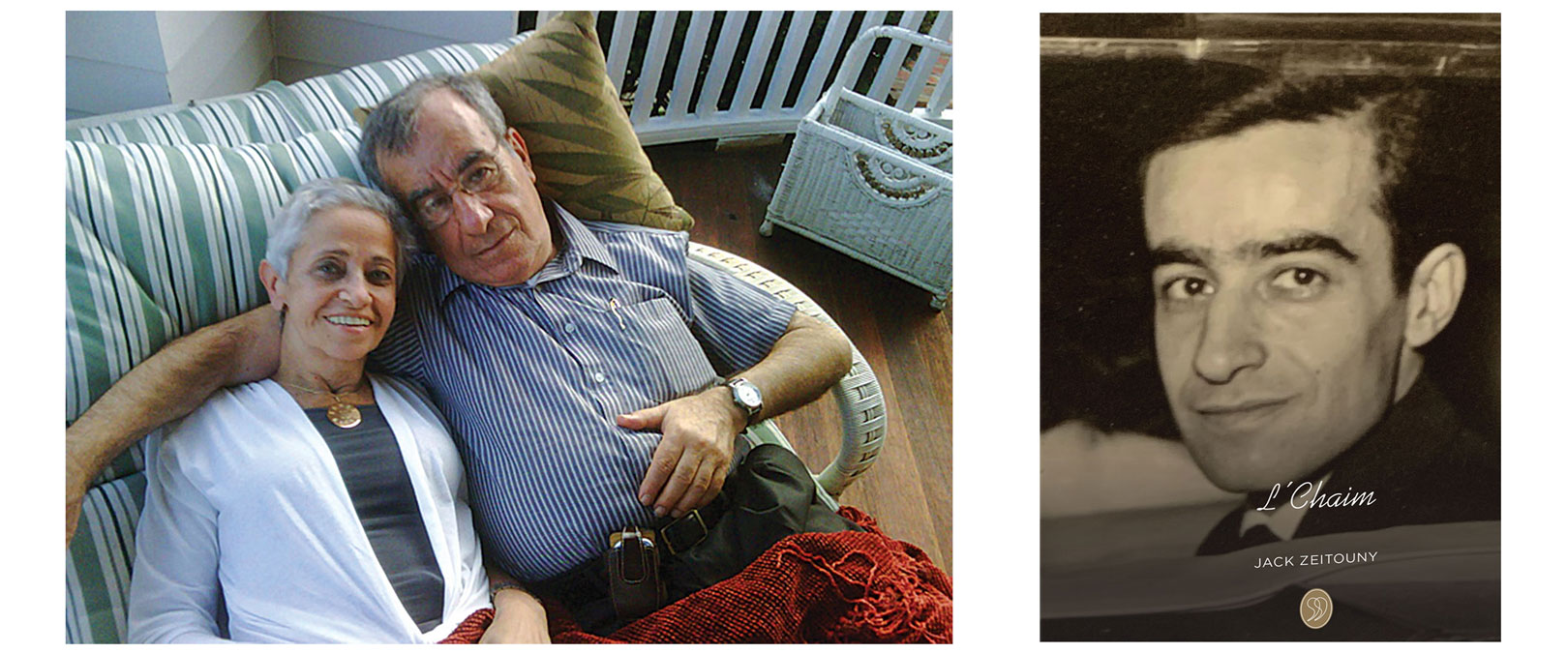

After years of hard work in America he was, in fact, able to build and provide for his children and grandchildren. When he and my mom bought their apartment in Florida, he felt he had grasped the American dream. He was so proud of it. It was everything immigrant dreams were made of. Retiring in Florida just like “real Americans” do. At that time we started to see a tiny glimpse of him putting his guard down, maybe for the first time enjoying what he had built but then, only a few years in, my mother, the love of his life died. It’s impossible to talk about my father’s death without speaking about my mother’s. Her death threw my father right back into survival mode. It was the place he was most familiar with and where he went when he was lost. Survival mode was his comfort zone. It was an ugly and stressful place, but that is where he knew how to live.

When he fulfilled his mission of putting my mother’s name on the front of the Magen David Yeshivah building, we thought for sure he’d be satisfied. It was documented proof that he made it in America. Less than 50 years before that, my mom rode her bike to Magen David, because we didn’t have a car, and begged Rabbi Greenstein to give her children a chance in this American school. Even though we didn’t speak English and couldn’t afford to pay tuition, she begged him to trust her and believe they would make him proud. Less than 50 years later, her name was on that building.

Survivor mode made my father stubborn and paranoid and difficult at times. It took wisdom to understand that who he was, was formed by his story and it took patience to not react personally. It took love and sympathy to understand where his fear came from. He needed that from all of us.

If I had another day with my father, I would ask for forgiveness. Forgiveness for the times I didn’t have enough patience and forgiveness for the moments I didn’t have the wisdom. I’m grateful for the people in his life who always had those things for him. He was shown tremendous respect by the neighbors on the block where he lived—neighbors who cooked for him, brought him flowers, and played sheshbesh with him on the porch. He received visits from men and women half his age, who felt a connection to him and tenants who called to ask about him and cried when they heard of his passing. He definitely had his people. I’m thankful to all who were able to see through his hard exterior, and have sympathy and respect for a man with a tremendous story. Rest in Peace Papi.

Bertha Sabbagh is a community member.