Twelve people, the Kassab and Shama families, in an early group to show up at the Shamosh House in 1950.

Sarina Roffé

The Shamosh family of Iskenderun began helping refugees in the late 1930s when they helped Eastern Europeans escaping Nazi Germany. After World War II and the creation of the state of Israel, the family helped Syrian refugees escape the persecution and restrictions placed on Jews. Between Hakham Yaakov and his eldest son, Harun Shamosh, more than 3500 people were assisted after they left Syria. This is their story.1

Iskenderun is a city along the Mediterranean coast, just northwest of Syria. Hakham Moses Tawil sent Hakham Yaakov Shamosh there from Aleppo to serve the community in 1932. He was the rabbi, the hazzan and the shokhet. After a few years he went back to Aleppo, and brought back his bride, Mazal Esses. Their son, Harun Shamosh, was born in 1936, the eldest of eight children.

Until his death in 1970, Hakham Yaakov arranged for many escapees to get to Israel. Eventually, his son Harun took over the mission, along with other family members. Iskenderun played a big role in helping Jews who escaped over the mountains from Aleppo into Turkey.

There were many restrictions for Syrian Jews. One of them was the restriction on travel, and the fact that you could not travel more than three kilometers from your home without permission. Jobs were lost and there were boycotts on their businesses. Many people tried to escape. Doing so involved baksheesh (bribe), smugglers and a dangerous escape route. For the Jews of Aleppo, the nearest border was through the mountains to Turkey. Since Hakham Yaakov had come from Aleppo, many families knew him and found their way to his home in Iskenderun.

In 1948, Syria only gave passports to its citizens. From about 1950-1960, some paid the Iranian consulate for passports. Those who were able to get Iranian passports went to Iskenderun and took a ship from there to Haifa. The ship only came once every 21 days.

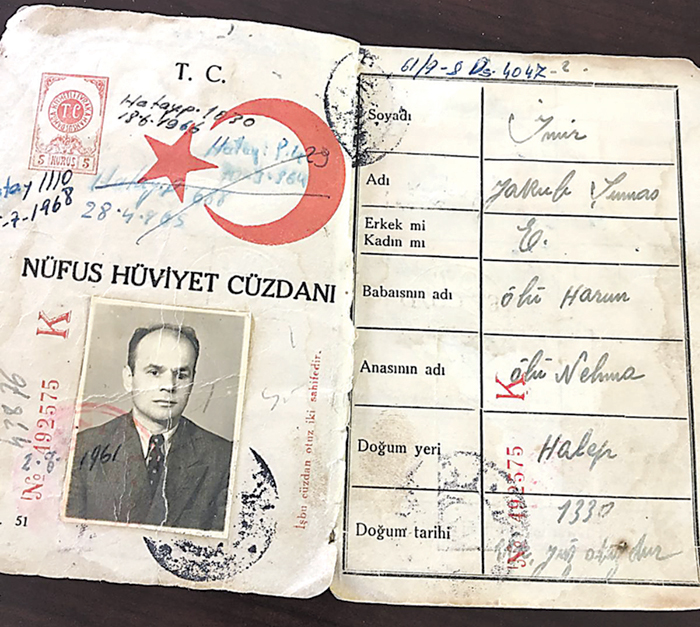

Syrian Jews started to show up at Hakham Yaakov’s home in 1950. A group of 12 people from two families managed to get over the border into Turkey and came to his house with no money, filthy, dirty from traversing the mountains.

Hakham Yaakov arranged for them to get cleaned up and got a bus to take them to Istanbul – a 20-hour drive. They had to be escorted by a family member because they had no papers and only spoke Arabic, not Turkish. Hakham Yaakov found a place for them to stay in an old hotel. Hakham Yaakov went to the rabbinate in Istanbul for guidance. Then the refugees were taken to the Israeli consulate and arrangements were made for them to go to Israel. This process of using the Iranian passports went on for four to five years.

The rabbi often invited Jewish people to their home for Shabbat. One week there was a couple who claimed to be engineers working at a local cement factory. Hakham Yaakov’s wife was suspicious. As it turned out they were Mossad agents looking for a partner to help the Jews leaving Syria, Hakham Yaakov became that person. The agent instructed Hakham how to get people over the border.

Those who escaped Syria had no entry visa because they came through the mountains and crossed the borders illegally. Before individuals could leave Turkey, a person needed an entry visa. The issue of getting entry visas posed a problem.

Hakham Yaakov went to the police and asked what to do, explaining they could not go back and were refugees. From about 1954 until 1975, there was an arrangement whereby the police – for a fine of 70 lira – would issue entry visas good for 30 days to those who escaped. With the entry visa, the refugees could get a laissez passe (travel papers) in Istanbul and then go to Israel.

Each time a group of escapees showed up at his door, Harun or another family member would take them by bus to Istanbul.

After Hafez al-Assad became President of Syria in 1971, many families were escaping. Harun and the family were busy. Harun became well known for his work, not just his connections kept him safe.

Harun worked with trusted smugglers who got Aleppan Jews across the border into Turkey. They often used a code, like half of a photo or one earring. If the smuggler had the other half, he could be trusted not to say Harun’s name. The signal was always different.

Jack Imir, Harun’s son, remembers a Turkish Muslim smuggler who was often at their home. He smuggled goods across the border in both directions. He was sent to homes in Aleppo and started to bring people to Turkey. The smuggler was trusted, and he brought families several times a week. As more and more people were leaving in the 1970s, the Shamoshs were able to recruit more smugglers to assist. The smugglers knew what they were doing and were loyal to Harun and worked for them for many years.

Some people had the funds to pay smugglers on their own and others had to be helped with money. A lot of money was used for bribes or baksheesh. All involved wanted a piece of the action and Mossad bribed many government officials.2

Usually, people were smuggled over the border at midnight, when it was dark and the guards were more relaxed. The process was that the smugglers told the refugees only to wear the clothes on their back. They were not to bring any identification. The smugglers were often smuggling other items as well.

Border patrols were looking for smuggling of merchandise, not people. Smugglers were always paid in cash. Harun and his family said the refugees arrived at his home in the middle of the night, about 3 a.m. They walked for days in the mountains, in mud, and arrived at his home filthy and exhausted from the trip. Babies were carried and drugged to keep them quiet. They arrived hungry and needed to be fed.

Occasionally, if someone was caught at the border by the Turkish border patrol, the smugglers would run away, tell Harun Shamosh what happened and he would go to get them released. This happened many times. One family that he helped get released, met him decades later in Israel.

The Shamoshs bought the refugees new clothing and provided shelter until arrangements were made for them to go to Istanbul and then Israel. Shamosh tried to make same day or next day arrangements if he could. At times, the people were coming almost every day and each family member helped out. Harun’s wife, son and daughters often made the trip to Istanbul or did the shopping for clothing.

A separate operation began at the behest of Eddie “Whitey” Sitt from Brooklyn, New York. Hakham Shaul Cohen of Turkey was a friend of Sitt and told him what Harun was doing. In 1971, Sitt went to Turkey and offered to help. Sitt wanted the refugees to come to New York. By the mid to late 1970s, a separate operation developed whereby Sitt sent signals for families that wanted to go to New York. These were people who had families in New York and had been separated. Those refugees who wanted to go to New York had to pay their own way. The Jewish Agency only paid smugglers for the families going to Israel.

By 1979, the 70 lira fee became a thing of the past. About 1980, they switched the operation to Antakya, where the Jemals, Esther’s family lived. Iskenderun became too dangerous for the refugees. Antakya is about 35 miles from Iskenderun but closer to Aleppo. Refugees went to the police station in Antakya, declared themselves to be refugees from Syria who wanted to go to Israel. The police sent them to a State Department office and Harun Shamosh was asked to handle their transportation to Israel.

By 1986, there were fewer people escaping Syria. But Mossad wanted him to stay until 1992. Harun would meet Mossad agents in the Dan Tel Aviv and Harun would give them reports. There are 60 years of reports about the Shamosh family and their work with the Syrians who escaped.

Harun and Esther emigrated to New York in 1992, the year of the exodus when Syrian President Hafez al-Assad lifted the prohibition on travel.

1 Based on interviews with Harun and Esther Shamosh with daughter Rutie Haser on April 2024; Jack Imir on December 31, 2023; Harun and Esther Shamosh with daughter Nurit Sousson on June1, 2024 and October 9, 2024

2 Author has no confirmation from Mossad. However multiple sources interviewed for this book noted the role of Mossad in Turkey and in Lebanon for assisting escaping Syrian Jews.

A genealogist and historian, Sarina Roffé is the author of Branching Out from Sepharad (Sephardic Heritage Project, 2017). A version of this article will be included in her upcoming book: Syria – Paths to Freedom. Sarina holds a BA in Journalism, and MA in Jewish Studies and an MBA.